|

| Washington DC 1912 |

|

| policeofficer using callbox |

Fighting

Crime with Radio,

by

Harry Blesy

Around 1930 Police Departments all over the country were investigating the possibility of utilizing radios to help

combat crime. Before this time signal-lights, sirens and/or call boxes were the likely way policemen, who were not in the

station, could be alerted of criminal activity. The criminal was usually long departed from the scene by the time an officer

arrived.

Radio

Stations Broadcast to Police

AM broadcast band radio was all the rage in the 1920’s. In some of the larger cities around the country, AM broadcast

stations engaged in conducting tests for the police departments by making one-way transmissions to police scout cars. Chicago

radio station, WGN, did this for a few months in 1929. During the test the switchboard operator at the Chicago Police Department

would telephone the WGN studios with their dispatch requests. WGN would then broadcast a “police alarm” to the

radio (receiver) equipped police car. Chicago Police also relayed requests to WGN for a few suburban police departments. It

didn’t take long for the police to determine that the concept of utilizing radios for receiving police calls had plenty

of merit.

Chicago

Police On-the-Air

(Detroit

Police was the first in 1928)

In 1930, Chicago police installed their own transmitters in three locations around the city and dispatched

calls to their own squads as well as to some suburban squads. They transmitted on 1712 Kilocycles which is just above the

regular AM band and just into the bottom of the shortwave band.

Early

problems with first police radio.

There were some problems: Signals didn’t saturate the total targeted area, such as under viaducts. Noisy reception

was a problem as well as interference as more departments around the country joined fight against crime with radio and were

assigned the same frequencies. It was a mess; departments in different states at times would interfere with one another.

Even if the stations were located far apart, propagation of signals on those frequencies was such that the transmissions

would travel hundreds of miles especially after sunset. The radio dispatcher had no way of knowing if the policemen heard

the one-way transmission or even if the officer was near his radio. Because of the signal interference an officer might mistakenly

respond to another department’s broadcast, especially if the two towns had identically named streets. Departments started

using their own unique sounding gongs before and after a dispatch in an attempt to alert their ‘own’ officers.

The

Public is Entertained.

Listening in on police calls became popular entertainment for anyone who had a shortwave receiver or sometimes even

just regular broadcast radios. Radio magazines regularly published lists of police departments that were transmitting. The

lists contained the police agency’s call letters and frequency. The police departments knew that their transmissions

were not private and some departments felt that honest citizens listening in might be of benefit for obvious reasons. Other

departments felt a need for communications confidentiality, but their depression time budgets usually did not allow for technological

improvements.

|

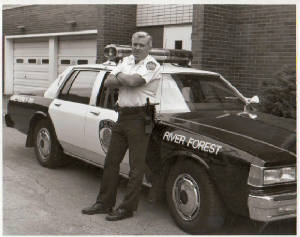

| River Forest Police on Ultra-shortwave |

Two-Way

Radio

Police agencies became desirous of a two-way radio system which would allow the officer in the squad car the capability

to talk back to the dispatcher as well as to communicate with the other squads. Even if a department had the funds, mobile

transmitters did not exist. Because such equipment could not be purchased, a few innovative police departments enlisted the

aide of radio technicians who struggled with the six-volt electrical systems and high current drain to design practical vehicular

transmitters. These agencies applied for “experimental” licenses which allowed them to engage into research and

development, on what was called the “ultra short-waves” (around 30 to 42 Mc/s). In the 1930s that area of the

spectrum was felt to be relatively secure from criminal ears.

The

First Two-Way Police Radio System

In 1933 the Bayonne New Jersey Police Department became the first agency in the country to implement a 2-way radio

system. In 1934, Highland Park and River Forest Police led the way in Illinois with their two-way systems. Detroit, the police

department that had the reputation for pioneering the police radio was not able to accomplish two-way operation until 1934.

The cost of a mobile transmitter-receiver at that time was around $700-$800 which was more than the cost of an automobile.

The Chicago Police Department continued to transmit on 1714 Kc/s throughout the

1950’s although they did manage to equip their cars with transmitters on vhf in 1942 thereby instituting a ‘duplex’,

two-way radio system.

Public

Service band(s)

In 1937 the FCC officially allocated 30.58-39.9 Mc/s for two-way police radio use. Eventually this band of frequencies

became known as the 30 to 50 Mc, VHF Low, Public Safety Band.

At that time the FCC also issued regulations which appear to defy logic. They issued a rule which told the police they

couldn’t transmit to points that they could not reach. Police stations were also prohibited from contacting other stations

that were located in the same telephone exchange area. (Trying to understand what motivated the issuance of such a rule, I

could only speculate that it might have had something to do with keeping the radio congestion down or possibly the phone company

had some influence over the FCC. I don’t think it was issued in the spirit of fighting crime.)

Rural and state police agencies migrated to this VHF-Lo band in the 1960s and metropolitan police departments

congregated in the 150-170 Mc, VHF High, Public Safety Band. The characteristics of radio waves on the higher frequencies

allowed for better reception in the cities. Those waves tend to do better around the buildings and other structures.

Modern

Technology

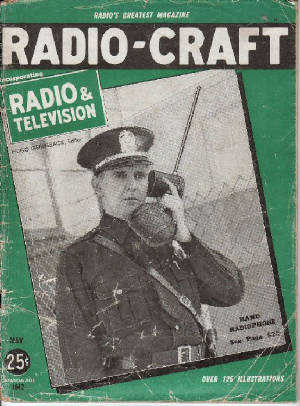

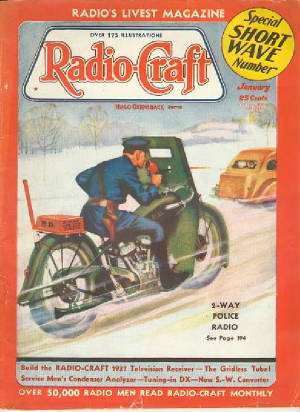

Back when the radios still operated with tubes the police were also installing them on motorcycles. ‘Real-time’

radio teletype was used until a unit was developed that ‘punched up’ a paper tape before going on the air. The

tape was then fed into the teletype machine and it sent out the data at a high speed, thus conserving air-time. The first

portables manufactured for police use were heavy field units with a telephone handset on the top. In the 1960s police started

using brick sized portables which were then available.

Police communications has evolved into very sophisticated, modern, ‘crime fighting’ networks. The police

now use small, epaulet attached, portable radios in addition to, or sometimes even replacing, mobile transceivers. Thanks

to the miniaturization of circuitry, smaller, more efficient batteries, and use of repeaters, the HTs (handy talkies) have

become quite small. Other technological advancements made available for police communications are: satellite and mobile repeaters,

encrypted transmissions, MDTs (vehicular digital transmissions w/keyboard), mode of transmission variations such as ACSB (amplitude

compandered sideband) and trunking systems. Many police departments have vacated the VHF-Lo and VHF-High bands for much higher

frequencies.

The general public has also been treated to further advancements in the ‘sport’ of monitoring police calls.

Tunable receivers replaced early converters and they were superseded by crystal controlled receivers. The next technical revelation

was the crystal controlled scanning receiver and that was eventually followed by programmable scanners. These radios allow

the listener to monitor a multitude of departments with just one radio and without constant manual tuning. A variety of features

are available on a modern scanner including the capability to follow “trunked” transmissions.

Harry Blesy,

is a retired River Forest police lieutenant.

He served for over

27 years beginning his career in 1967 when the mobile radios had vacuum tubes and the officers did not yet have portable radios.

His department was one of eighteen police departments that shared one very crowded VHF frequency. Harry was working

the night a police officer was kidnapped and murdered by armed robbers who had just got into their own vehicle after ‘dumping’

a work car. Blesy heard the unfortunate officer’s last transmission on the radio when he tried to ‘call in’

the license plate of the vehicle he was stopping. In another town there was an unrelated report of an armed robbery which

covered the doomed officer’s words. The other town’s robbery report was later discovered as not bona-fide. This

incident was responsible for many improvements of the police radio systems in the western Chicago suburban area. Blesy later

was appointed in charge of communications. He redesigned and modernized the River Forest communications center in the 1980s.

He supervised the implementation of computer-aided dispatching and the first amplitude compandered side band(ACSB) police

system in the U.S.

|